Survival of the Fattest

Learn why Rupert Pupkin/Robert De Niro in Martin Scorsese’s wonderful film The King of Comedy by no means is a loser, but the closest thing to the Nietzschean Übermensch. Read the true story of how the fat and ungraceful Martin Melin became the slim and fit heartthrob adonis of all Swedish mainstream womanhood—by winning the first Swedish edition of the international television reality show hit Survivor (Expedition: Robinson).

I have worked so very hard, I have kissed asses when called for, I have been politically correct. To no avail. As a last resort I have appealed to charities, to patrons of the arts, to the media, and even to politicians to acknowledge and champion my cause. But my life and my career are still going nowhere. What am I doing wrong? What path to the emancipation and empowerment of the individual will save me now that democracy won’t?

If you fit the description above, take a lesson in how to turn your life around from two case studies—one from the world of fiction, the other from the real world—and discover that to you and your sorry kind, paradoxically, the recipe for social and professional success will never be to submit or to try even harder to go by the book, but to be audaciously anti-social and unprofessional.

Fiction: Rupert Pupkin

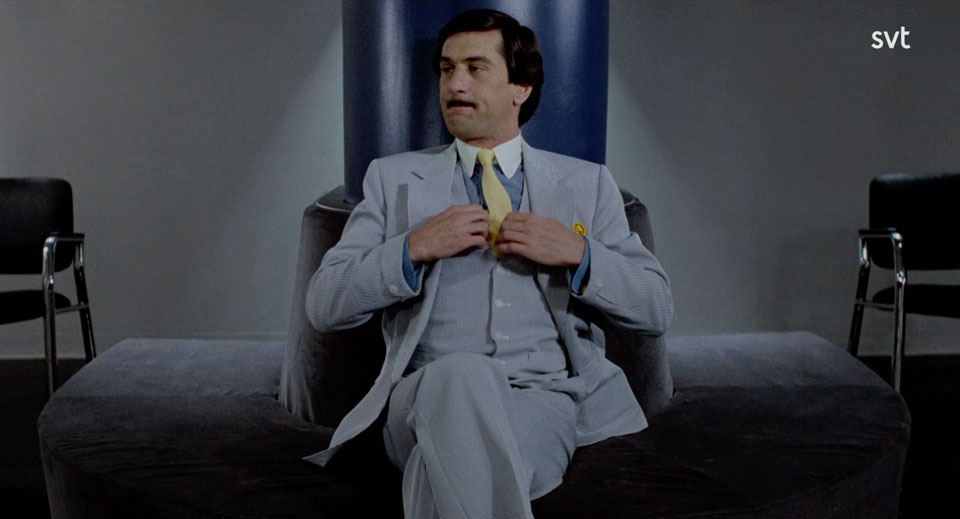

American director Martin Scorsese claims he was more or less talked into doing The King of Comedy (1983) by others. Robert De Niro, for one, was very keen on playing the protagonist. In interviews Scorsese does not go so far as to call the film a total failure, but he seems unconvinced of its qualities to this day. One wonders why, because—with the exception of having to listen to Van Morrison during the closing credits—everything about the film is perfect.

Of course, The King of Comedy owes much of its success to the screenplay by Paul D. Zimmerman. It tells the story of Rupert Pupkin, a 34-year old bachelor (played by De Niro) who wants to be a comic. He still lives with his mother and he practices his stand-up comedy routine in a mock television studio in the depressing basement of his mother’s house. In his daydreams he is world famous and best friends with his idol, Jerry Langford (played by Jerry Lewis), the host of a popular television talk show. Pupkin is convinced that Langford would offer him an appearance on the show if they could only meet. Rupert has no references or experience from comedy clubs, so understandably Langford’s secretary turns him away, time after time. After a number of fruitless attempts to get past security, Pupkin is thrown out on his ear. In a final, desperate attempt to break into show business Rupert kidnaps (!) Langford. But he asks no ransom. All Pupkin wants in exchange for Langford’s life is ten minutes for a stand-up monologue on his show. The television network concedes (!), and Pupkin gets his ten minutes nationwide.

After the performance, Langford escapes and Pupkin is immediately arrested and sent to jail. At this point, the film is almost over, and the moral of the story is, everyone assumes, Crime does not pay.

No one in the audience is surprised or sorry by the outcome: Pupkin had it coming to him. The sentiments of the audience have all along been against Pupkin. When Pupkin pesters Langford’s secretary not once or twice, but again and again, we are on her side and we suffer along with her. When Pupkin later gate-crashes Langford’s country estate, the audience is again not on Pupkin’s, but on Langford’s side when Rupert once again is thrown out on his ear. As the plot unfolds, Pupkin reveals a bad case of social dyslexia. He is obnoxious, ridiculous, tactless, and pathetic. His attempts to swoon the girl he loves, Rita, are ungraceful, nerdy, and conceited. The people in the movie want nothing to do with him and the movie’s audience cannot help sympathizing with them. Rupert is not likable. He does not deserve

and has not earned

success. (Rupert’s meticulously groomed hair and mustache, and his neat but slightly surreal wardrobe establish a visual metaphor for his social dyslexia.)

But—and this is the genius of the movie—one has, as it turns out, jumped to conclusions about the film’s purpose. The story does not end when Rupert Pupkin is sent to jail. Only seconds remain of the film’s running time, and yet a complete reversal of the plot—the peripeteia—is yet to come. In less than a minute we, the audience, are told the following: Pupkin spends his time in jail writing his memoirs. Because Pupkin’s ten minute monologue was seen by an estimated 87 million American households, and because Pupkin made headlines and magazine covers everywhere when the media learned of the spectacular celebrity kidnapping, Pupkin already is a household name, and his book becomes a bestseller. He is released from prison for good behavior after less than 3 years, with hundreds of dedicated fans greeting him at the prison gates. In the last image of the movie, Pupkin greets the ecstatic studio audience of his very own nationwide television talk show. Everyone who used to put him down now sucks up to him, simply because his notoriety and fame has made him bankable. This sudden and unexpected turn of events prove that the biggest joke of The King of Comedy all along was never on Pupkin but on us, the audience.

If you can’t get what you want by going by the book, you have to bend the rules. Given the right circumstances, crime does pay very well indeed. The King of Comedy is, however, not at all a film about decadence or moral decay in modern American society. The maxim crime does not pay

is not challenged per se. After all, Rupert Pupkin is sent to jail. His debt to society gets paid. The film does, however, suggest the option of considering crime nihilistically as investment and commodity: Rupert Pupkin purchases the benefits in breaking the law, and invests for the future by doing time (just like Nelson Mandela—morals, motives, and goals aside). Once the price is paid and the debt to society is settled, Pupkin is free to conquer the very society he has trespassed against, going on to become an American hero and superstar. In many countries (those with no capital punishment or life-long imprisonment), someone like Pupkin could even have use for murder—in full view of society and the judicial system—as a nihilist vehicle through which to achieve, in time, greatness and success.

This message is indeed subversive, but it would have been lost on the audience, had not 99% of the film’s running time been invested in establishing and insisting on Rupert’s impossible character. It would have been just another American dream success story, in which the talented and good-hearted hero—undeservingly

held back by society and envious colleagues—refuses to give up, works even harder, and in the end, deservingly,

gets what he wants. Rupert Pupkin indeed deserves

nothing. As a comic he is mediocre. He is not funnier than any other wannabe comic, and he certainly does not possess the character and good nature of a person who the public feels

has deserved

success. Pupkin’s personality ensures that neither idle chance nor luck, nor hard work and diligence, will win him any favors or privilege—not in America nor anywhere else. The normal path to a career in comedy—via stand-up comedy clubs, television, and film—is thus never an option open to Rupert. Charitable or philanthropic organizations could not assist him in his repeated attempts to escape his social and professional predicament. Not even a brilliant piece on him by a Pulitzer Prize winning reporter could help him. Nor could, discouragingly enough, the institutions of democracy. No one will ever come to the rescue of a schmuck. In the minds of the public, there is no greater crime than to be, like Rupert Pupkin, a loser. The American dream is not for the Rupert Pupkins of the world.

Historically, neglected and disrespected groups in society have, through legislation or revolution, worked themselves into political arenas, making society more responsive to their needs. For the Rupert Pupkins of the world joining such a group is no option. Nobody wants them to join. To transcend the society and, not least, the personality in which he is a prisoner, Rupert Pupkin has to fight alone.

Fighting all your battles alone is hard, of course, but at least you do not have to submit to a group manifesto or simplistic common denominator compromises. He who conquers alone does not have to settle for membership in a society already defined and upheld by others. He can create a brave, all new world for himself, just as Jesus, Napoleon and Stalin did. Who would have thought: Rupert Pupkin—the Nietzschean, nihilist transgressor of democracy; Rupert Pupkin—der Übermensch.

Fact: Martin Melin

September 1997. The Swedish media is going berserk. Details about a new television game show—yet to be aired—have leaked to the media, and so enraged and appalled journalists that a nation-wide campaign to ban the show is started by the sensationalist evening tabloids. The show that has created such commotion, Expedition: Robinson (as in Robinson Crusoe), is based on a format by a British production company, Planet 24 [Note added in 2000. Original title of the format: Survive. The same format on American TV is called Survivor.], in which sixteen contestants—adults of both sexes, of different ages, and from different walks of life—have been selected by a casting committee to spend six weeks during the summer of 1997 on an uninhabited island in the South China Sea. Everyone helps and shares in finding food and building shelters. A passive TV-crew is registering every step and every conversation, much like The Real World, MTV’s popular show from a few years back. The object of the game and the program is to select one contestant as a modern-day Robinson Crusoe. He or she wins a substantial cash prize. In each weekly one-hour episode the television audience is invited to watch not only how the participants deal with their daily trials to find food (which turns out to be the contestant’s biggest problem), but also to deal with damp clothes that never dry, shelters that fall apart, and of course the requisite social frictions that emerge. There are also typical game show competitions, intentionally silly and tongue-in-cheek, including tropical island-style games such as bowling with coconuts. But the dramatic high point of each episode is the vote to send one contestant home. Each contestant explains why he or she thinks so-and-so should be sent home. The majority rules. Like ten little indians, they grow fewer with each passing program.

In the months between the pre-recording of the show and the actual broadcasting, something unexpected happens. The first contestant to be voted out and sent home, a young man, unfortunately commits suicide. The man’s family blames the Darwinian process of selective survival, the vote to punish (rather than to reward) a member of the collective. Columnists and opinion makers join forces with the family of the deceased to stop the show.

In spite of everything, the first episode of Expedition: Robinson is aired as planned on 13 September 1997. To lessen the attention around the young man who took his life, and in an attempt to muffle the expected outcry in the media, the provocative element of each contestant spelling out his or her reasons for wanting to get rid of a certain contestant is not shown. To no avail. The reviews are, as expected, devastating. The broadcasting schedule for the remaining episodes is halted and the television executive responsible is left with no choice but to resign.

Still, six weeks on location in the South China Sea costs money. Not to broadcast all episodes would be a waste. Presumably, each contestant has made a mature and conscious choice between the advantages (money, exhibitionism) and disadvantages (humiliation) of participation. This mitigates against the media’s original accusations of Darwinian exploitation. After things have cooled off, the remaining episodes are finally aired, beginning October 4, 1997. At first there is some grunting in the media about this, but over time the aggressiveness dies down as the ratings for the series go up. As public opinion sways in favor of the show, the same sensationalist tabloids that cried wolf the loudest start doing phone-ins, interviews and biographical portraits on the contestants.

The reason for the show’s popularity is the intriguing sociological perspective. In the first episodes, those voted out are not those who are the least successful at fishing or hunting or building huts, but those who are least liked, the misfits. Over time, voting patterns change, and the Swedish television audience is stupefied when the majority—the mediocre players—start to conspire against the strongest and best liked players. For example, the young man whom everyone expects to win because of his good nature, method, temperament and strength, is cast out at an early stage of the game. Scheming and intricate survival tactics lead to unexpected results. The fewer the contestants, the less predictable each vote gets. Fabulous entertainment.

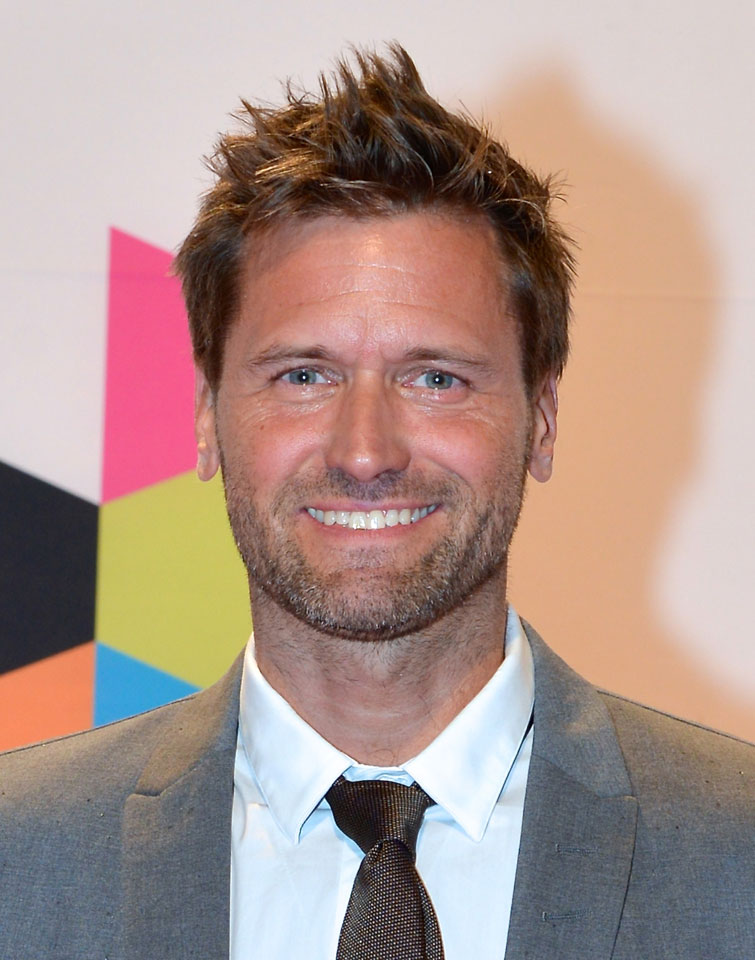

December 13, 1997. The last episode of Expedition: Robinson is broadcast. Martin Melin, a thirty-something chubby police officer from Stockholm wins the game and SEK 250,000 (USD 30,000). He has lost some 40 pounds (20 kilos) in six weeks. He is no longer fat. On the contrary, he flaunts an impressive torso. He is not anorexic-looking like the rest, He looks just right. Investing six weeks in starvation and total loss of privacy on a game show whose format has challenged every public notion of decency, good taste and political correctness, turned out to be an excellent choice for flabby Martin Melin. He is not only the champion, but he has completely reinvented himself. No longer the bloated lard-ass cop he once was, his life will never be the same again.

The tabloids back home write about his victory and homecoming, about the break-up with his girlfriend, about what he is going to do with the money, as well as about the fact that he will leave the police force (so much for the calling to serve the public) to become co-host of another, equally popular game show. And by January 1998, editors and agents have had time to work Martin Melin into the schedules of every newspaper weekend supplement, and every television celebrity game and chat show. Melin is giving sex tips on tv and taking his shirt off in ladies magazines. He invites photographers to his new downtown bachelor pad. He is seen at every opening and celebrity function. He dumps his nice but ordinary girlfriend once he gets to rub shoulders with stars and media moguls. He is soon seen with a new, more glamorous girlfriend at his side. This is indeed the high life.

The buzz does not die down. Journalists do some investigative reporting and reveal unknown things about the young Martin Melin. It turns out that he was once a slim, not yet overweight, long-haired, permed, self-conscious looking teenage model who posed occasionally for covers of teenage romance magazines. While these news seem on the surface to be merely anecdotal, such revelations shed light on the nature of this survival pro. He was never just

a cop who for a laugh happened to audition for a show. He had a taste for public exposure and glamour in him long before Expedition: Robinson came along.

It is no accident that it is the Survive/Survivor format which propels Martin Melin out of the cul-de-sac of the sub-middle class career prospects of the police force and into a totally new existence. Because the media perceived Expedition: Robinson to be ruthlessly Darwinian and a politically incorrect challenge to every notion of decency and good form, there was much at stake and much to loose. The show cost one television executive her job, and some would claim that it cost the life of one of the contestants. It had become snuff television; it had literally become a matter of life or death. But because there was so much at risk, there was also so much more to gain. Like the triumph of Rupert Pupkin, the fate of ex-cop Martin Melin suggests, that if the price is right (pardon the pun)—if the social and political risk taken is high enough—the sky is the limit for what a television show might produce for the participants. Martin might very well have made more money on some other game show, but he would not have lost 40 pounds and reinvented himself in the process, and he would not have become the adonis of mainstream Swedish womanhood that he is today.

Many people win cars and kitchen appliances and mind-boggling cash prizes on game shows every day, but their names or faces never linger in anyone’s memory. They are replaced the very next day by new names and faces. The Jeopardy champion who dreams that his victory will not only pay off in cash, but also in his private life and career, will always be disappointed. This is equally true for the contestants in shows like Gladiators who will never enjoy an off-screen triumph comparable to that of Martin Melin.

There is no social or intellectual risk-taking involved in subscribing to formats such as education is good

(Jeopardy) or physical fitness is good

(Gladiators). The public shows little interest in those who excel, if all they do is excel in subscribing to values already praised by the establishments (and purveyed through the universities, gyms and sports clubs). Such submissive scholars or athletes will do as entertainment (on Jeopardy or Gladiators), but the public will never reward playing it safe with great admiration or worship. No pain, no gain.

Postscript

Some post-deadline news: Swedish tabloid Aftonbladet reports (August 1998) that Martin Melin’s official taxable income in 1997 was SEK 812,000 (not counting the SEK 250,000 cash prize from Expedition: Robinson) compared to a taxable income of SEK 246,600 in 1996. The final episode of the show was aired on December 13, 1997—with only two weeks to the new year 1998. This means that he made some SEK 566,200 (again, not counting the cash prize) in the first two weeks immediately following the competition alone! The figures of 1998 are not yet official.

Sweden is recording its second season, and Denmark its first season of Survivor this summer (Germany, Holland, United Kingdom and United States are expected to follow suit in the future). However, according to some sources, the format and rules have been changed, to make this year’s and future editions less provocative, less Darwinian as it were. This means that in the future there will certainly be fewer deaths and casualties associated with the format. But, this also means that the media springboard effect simply from being a contestant on the show disappears. If the contestants of this year’s editions hope to repeat Martin Melin’s off-screen success, they will be disappointed.

Appendix 1999

E-mail to Mikael Askergren signed Martin Melin, the subject of one of the two case-studies in the text above, commenting and correcting and completing the figures in the postscript:

In the e-mail below Martin Melin estimates his income from winning the Expedition: Robinson competition, and from becoming a celebrity, to be one million Swedish crowns (SEK), to date—which only confirms my argument in Survival of the Fattest

. The e-mail below is reproduced with kind permission from Martin Melin:

Från: Martin Melin

Till: Mikael Askergren

Ämne: Hallå där!

Datum: lör 04 sep 1999 22.24

Hej Mikael.

Jag fick en sida skickad till mig där du hade skrivit en artikel. Till vad vet jag inte. Den var intressant och riktigt bra. Du kommer att gilla Lasse Lindroths bok för du har sammanfattat den (boken) ganska bra i och med din story

om mig.

Några fel var det men va fan...fast ändå; jag tjänade 812 000:- 1997 och det var inklusive 530 000:- som den faktiska prissumman var (250 000:- efter skatt) sedan var de andra 280 000 från polisen. Så det var inte speciellt mycket pengar ändå. Men mellan dig och mig så gav Robinson-vinsten mig ca en miljon, före skatt (till dagens datum) men också en massa, ovärderliga upplevelser.

Ha det så gott

Martin Melin

Survival of the Fattestwas published in Merge Magazine (Stockholm, New York) #2-1998. The first part of the text

Fiction: Rupert Pupkinwas also published in Art-Land International Magazine (Copenhagen) #1-1999 under the title

What Path to the Emancipation and Empowerment of the Individual Will Save Us Now that Democracy Won’t?

What Urge Will Save Us Now that Sex Won’t?) also in a text about Dirty Harry, Clint Eastwood, and the late Swedish politician and urban planner Hjalmar Mehr:

What System Will Save Us Now that Democracy Won’t?

Monarchy Rules

Illustrations

• Martin Melin, overweight cop turned sex symbol of Swedish mainstream womanhood. Photo by Frankie Fouganthin (2013), Wikimedia Commons.